When Mom died, she left us a house full of stuff she couldn’t throw away.

My brother and I invited relatives to come over and take what they liked. What about the rest? We both lived out of town, so an estate sale seemed unrealistic.

We could put almost everything into rented dumpsters, but the last time we did that, trying to reduce clutter for Mom, she accused me of throwing away a musty piece of Samsonite luggage that contained $10,000 in cash.

I did throw out the luggage. I’m not sure what to make of the $10,000 in cash.

Boxes of Junk via UPS

With Mom now gone and my brother and I preparing to sell the house, I packed things like old Sports Illustrated magazines, moldy high school yearbooks, and my “Snoopy Sniffer” by Fisher-Price, which walked like a happy beagle if you pulled it from a leash. I filled dozens of boxes and took them to the local UPS store, which charged me nearly $3,000 to take them to my house 1,000 miles away.

It was worth it.

For several years, I couldn’t touch the boxes stacked neatly on a pallet, wrapped tightly in plastic. It all sat in my garage like an immovable monument to an emotion-filled past I didn’t want to face again.

When my son offered to help, I accepted and broke through.

We took the boxes from the garage to our finished basement, where I went to work sorting and trashing, pausing now and then to reflect on something interesting from our dysfunctional family. We believed the root cause of that dysfunction was a husband and a father who couldn’t hold his liquor or a job.

Financial Insecurity Sucks

Financial insecurity put pressure on Mom to hold multiple jobs to pay for the mortgage and put food on our table. It burdened me because I was the oldest who wanted to protect my emotionally distraught mother.

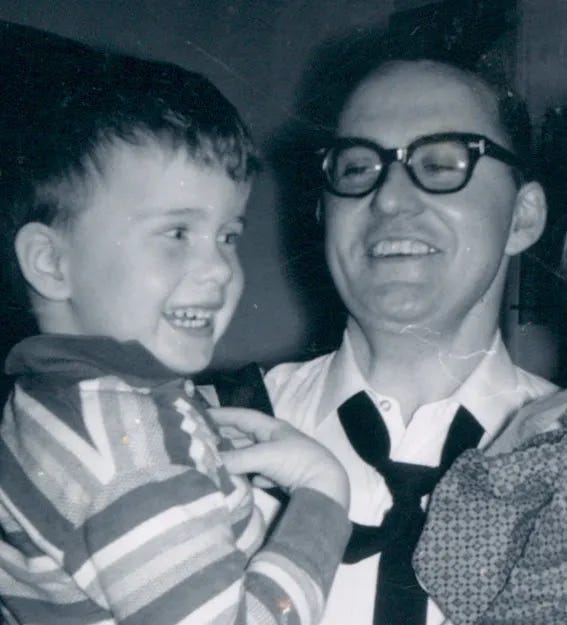

My anger toward my father slowly grew until it was hot lava coursing through my veins. I got counseling in my 20s, and we reconciled in my 30s, taking a Caribbean cruise together.

As I sorted, roughly 80 percent of what I touched ended up in a Hefty garbage bag destined for the dump. I spotted a spiral notebook with a blue cover that had no markings on it.

Hmm. Maybe it’s still usable.

I thumbed through the notebook as if it were a deck of cards. I stopped cold when I saw something written smack dab in the middle.

The Big Find

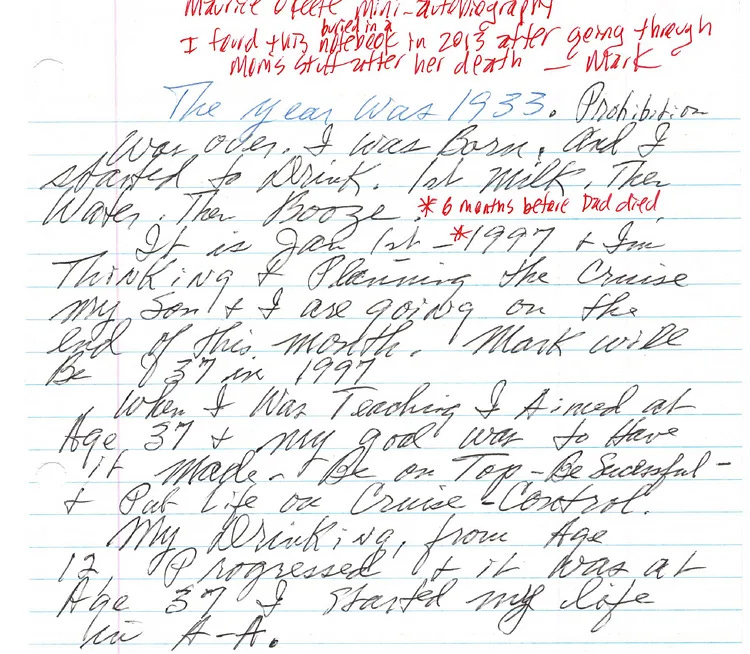

It was my father’s distinctive handwriting, six pages of it, single-spaced, under a title: “My Autobiography.”

I nearly gasped. I looked for a date and found January 1, 1997, six months before he died instantly in our house from a blood clot at age 64, rocking my world.

Why would you write your autobiography long-hand and start it in the middle of a spiral notebook without telling anyone? Dad was unorthodox.

Dad’s Intro got my Attention

His introduction was provocative:

“The year was 1933. Prohibition was over. I was born, and I started to drink. First milk, then water, then booze.

It is January 1, 1997, and I’m thinking and planning the cruise my son and I are going on the end of this month. Mark will be 37 in 1997.

When I was teaching I aimed to age 37, and my goal was to have it made, be-on-the-top-successful, and put life on cruise control.

My drinking, from age 12, progressed and it was at age 37 I started my life in AA.”

The rest of his autobiography focused on alcoholism, his powerlessness to defeat it and the Higher Power he and others turned to every Tuesday night in an Alcoholics Anonymous meeting he attended faithfully at Trinity Lutheran Church.

In high school, I learned about the six classic literary conflicts, such as Man vs. Society, Man vs. Nature and Man vs. Technology. This was the first story I read about Man vs. Alcohol.

Hot tears streamed down my cheeks, dripping on the notebook. Reading Dad’s narrative in his own words did something that counseling sessions could not.

It altered my point of view. I saw his life struggle in a fresh light.

Captain Obvious: I’m glad I opened that notebook before throwing it away.

New Vantage Point Changed My Perspective

A writing coach once taught me that every successful narrative follows a simple formula: a protagonist encounters a challenge and finds a resolution.

When the resolution is sad, the Greeks called it a tragedy; when it is happy, a comedy.

I had always seen my father’s story as a tragedy.

After reading his autobiography, I saw it as a comedy.

Reading Dad’s journey from his vantage point changed MY perspective and my life. It’s not how you start. It’s how you finish.

In the end, Dad Succeeded.

Dad ended well, in triumph, breaking the chains of addiction and creating a legacy of redemption that has trickled down to me, my sons and my grandsons.

For the first time, I felt glad Mom couldn’t throw anything away!

Dad was no longer a loser and a villain.

My father was a winner who beat a disease called alcoholism. Now he’s my hero.

On Father’s Day, I’m happy to tell my Dad’s true story, which I discovered in an obscure spiral notebook buried in a heap of household clutter.

25 years - that's so awesome Mark! I really like and respect that you were able to forgive your father and move forward in healing yourself. A great role model!

Discovering your father's unknown perspective on his life provided a relieving breakthrough in your perspective of him. Praise God! It only goes to show how vital it is for folks to try to be as transparent as possible with each other so that we don't harbor unfounded misconceptions about each other (or ourselves). "To know all is to forgive all," or as Oswald Chambers said, "Every time we judge another, we condemn ourselves (Romans 2:17–21). We must stop using a measuring stick for other people. There is always one fact more, in every person’s case, about which we know nothing."